Forging is a manufacturing process that uses external forces to plastically deform metals or other materials at high temperatures to obtain the desired shape, size and internal organization.

Introduction of Forging

A traditional and important manufacturing process used primarily for machining metal materials, but can also be applied to certain non-metallic materials. The process consists mainly of heating, shaping and cooling of raw materials to produce a part with specific dimensions, shape and mechanical properties.

Basic Concepts

Forging is the application of force to a metal or other malleable material to cause it to deform plastically under controlled conditions. This can change its shape, structure and properties, creating parts and products of high strength and durability. This complex process encompasses multiple techniques, including hammer forging and friction forging. The material is heated to a malleable temperature and then shaped by hammering, pressure or friction to obtain the desired shape. The basic concepts of forging include selecting the right metal material, controlling the heating and cooling process, and applying precise force. This ensures that the final product has the desired physical and mechanical properties.

This traditional process has wide-ranging applications in both manufacturing and the arts, and products are often characterized by high strength, durability, and precision. Forging is constantly evolving as it shapes metal. It offers artists and craftsmen a unique way to shape metal, demonstrating the perfect combination of traditional craftsmanship and innovation.

Historical Development

- Ancient civilizations: Early man used simple hammers and dies for forging, mainly for making tools and weapons.

- Middle ages: Started to use bellows and forges to improve heating efficiency, and developed some forging tools. The purpose of forging at this time was mainly for the manufacture of weapons and armor.

- Industrial revolution: The introduction of steam power made the scale and efficiency of forging equipment greatly increased, while the emergence of new materials (steel) and processes (heat treatment) also promoted the progress of forging technology. At this time, forging was widely used in railroads, ships, automobiles and machinery manufacturing.

- Modern forging: With the progress of science and technology and the development of automation technology, forging technology is further improved and optimized. Electricity and advanced mechanized equipment replaced the traditional hammer forging. The application of computer simulation and robotics makes the forging process more precise and controllable, while also improving production efficiency and product quality.

- Emerging technologies: As new materials and technologies continue to emerge, forging technology continues to evolve and innovate. The integration of emerging technologies, such as 3D printing, together with forging and the development of intelligent forging equipment, brings more innovation and possibilities to the forging field.

Principles and Processes of Forging

Basic Principle

- Plastic deformation: The core is to make the metal plastic deformation. That is, under the appropriate temperature and pressure, the crystal structure of the metal is deformed without rupture. This is because the bonding between metal atoms can be rearranged by external forces, allowing the material to change shape without destroying its internal structure.

- Unchanged volume: During the forging process, the total volume of the metal remains essentially unchanged. This means that the volume of the metal is equal before and after deformation, which is important for calculating material flow and deformation during forging.

- Temperature control: Materials are usually forged within a certain temperature range to ensure that the metal is in a malleable state. Heating reduces the hardness of the metal and makes it easier to shape.

Processes

- Material preparation: Select the appropriate metal according to the requirements of the product, and cut the raw metal into blocks of appropriate size.

- Heating: Heat the metal to the appropriate temperature. This temperature is usually higher than the recrystallization temperature of the metal to increase its plasticity and reduce its strength. The heating time needs to be precisely controlled according to the type of material, thickness and furnace temperature to ensure uniform heating and avoid overheating.

- Rough forging (preforming): For some complex parts, preforming operations such as rolling, drawing or upsetting may be required prior to forging. A block of metal is initially molded into an approximate shape by applying a large amount of hammering or pressure. This stage is sometimes called open billet forging.

- Forging: Further shaping of the metal with smaller hammer blows or pressures to obtain more precise geometries and dimensions.

- Cooling: After forging, the product needs to be cooled to stabilize it structurally and relieve residual stresses.

- Trimming: After forging, parts may require some trimming, such as edge cutting, punching, grinding or polishing, to achieve the final dimensions and surface quality required.

- Heat treatment: Appropriate heat treatment, such as annealing, quenching and tempering, is applied to the forged parts. This can adjust its mechanical properties, eliminate internal stress, and stabilize the organizational structure.

- Cleaning: Clean off the oxides and impurities on the surface of the parts, and if necessary, rust-proof them.

Classifications of Forging

Free Forging

A metal billet is plastically deformed by hammering, extruding or twisting without a preset die to form the desired shape and size. Free forging relies heavily on the skill and experience of the forging worker, as well as on common tools such as hammers and fixtures. This forging method is typically used to produce larger, heavier components such as large forgings, shaft parts, and wind turbine shafts.

Free forging is highly flexible and adaptable to produce parts of various shapes and sizes. However, free forging also has some drawbacks, such as relatively low productivity, high requirements for workers’ skills, and relatively high scrap rate. So, free forging is particularly suitable for small batch production and customized products.

Die Forging

In contrast to free forging, die forging uses a pre-designed mold to confine the shape of the metal. This method is often used to produce parts with complex geometries and high requirements for dimensional accuracy. Compared to free forging, die forging is more suitable for mass production and high precision requirements.

Die forging offers high productivity, good part accuracy and consistency, as well as a lower scrap rate. However, the initial investment in die forging is higher because it requires the design and manufacture of high-quality molds. For small production runs and complex shapes, the cost of molds may be higher. In addition, maintenance and replacement of dies are important factors to consider in the die forging process.

Hot Forging

Hot forging is a forging process in which a metal billet is plastically deformed at a high temperature above its recrystallization temperature. In this temperature range, the metal material has good fluidity and plasticity which allows it to be more easily molded and machined into desired shapes and sizes.

Hot forging is capable of producing high-strength, high-precision and complex shaped parts. Because it takes place at high temperatures, the metal flows well, which reduces energy consumption and tool wear during the forging process. Hot forging also improves the microstructure and mechanical properties of the metal. However, hot forging requires a higher initial investment, consumes more energy, and can produce greater fumes and noise.

Cold Forging

Plastic deformation of metal billets at or near room temperature. Compared to hot forging, it is performed at relatively low temperatures and requires higher pressures with more delicate operations to achieve plastic deformation of the material. This forging method is commonly used to produce smaller, more complex shapes and parts that require high surface quality.

Cold forging is capable of producing parts with high precision, high strength and high surface quality. At the same time, because it is carried out at low temperatures, it can reduce energy consumption and environmental pollution. It can also improve the microstructure and mechanical properties of the metal, as well as improve the utilization rate of the material and production efficiency. However, cold forging requires high precision and wear resistance of blanks and dies. In addition, the cold forging process may produce large internal stresses and residual deformation, which need to be eliminated by appropriate heat treatment and subsequent processing.

Warm Forging

Between hot and cold forging. Warm forging is usually carried out below the recrystallization temperature of the metal, but slightly above room temperature. This forging method combines the advantages of hot forging and cold forging, it can produce high-precision, complex shapes and high-quality parts. It is suitable for the production of small and medium-sized parts, and can balance the shape accuracy and mechanical properties.

Warm forging can improve the plasticity and fluidity of the metal while maintaining high strength and hardness. In addition, because the temperature of the metal in the warm forging process is lower, it can reduce energy consumption and environmental pollution.

Roll Forging

The metal is plastically deformed by using rollers to form the desired shape. In roll forging, the metal billet is continuously squeezed and bent through the gap between one or two pairs of rotating rollers. This process usually takes place below the recrystallization temperature of the metal. Roll forging is mainly suitable for the production of parts with long or annular cross-sections, such as bearings and shaft parts.

Roll forging offers high productivity, good part accuracy and consistency, as well as a lower scrap rate. In addition, since the fluidity and deformation of the metal in the roll forging process are continuous, internal stress and residual deformation can be reduced, and the mechanical properties and stability of the parts can be improved.

…

Metals for Forging

- Steel: High strength, wear and corrosion resistance. Different types of steel are suitable for different forging applications, such as carbon steel and alloy steel.

- Aluminum: Low density, good thermal conductivity and corrosion resistance. Commonly used for forging lightweight parts, such as those in aerospace.

- Copper: Good electrical conductivity, commonly used in the manufacture of electrical connectors, wires and some decorative parts.

- Stainless steel: Excellent corrosion and high temperature resistance. Suitable for the manufacture of parts requiring high corrosion resistance, such as pipes and valves.

- Alloy steel: By adding alloying elements (such as chromium, molybdenum, nickel) to improve its performance, so that its performance in high temperature, high pressure and other conditions more superior.

- Carbon steel: Favorable mechanical properties and processability, suitable for manufacturing some mechanical and automotive parts.

- Titanium: Excellent corrosion resistance and high-temperature stability, commonly used in high-performance parts in the aerospace field.

- Magnesium alloy: Lower density, suitable for the manufacture of lightweight parts, such as aerospace and automotive components.

- Nickel-based alloys: High temperature strength and corrosion resistance. Suitable for manufacturing parts in high temperature and high pressure environments, such as aerospace engine parts.

Equipment for Forging

- Air hammers: Use compressed air to drive the hammer head for striking, suitable for free forging and partial die forging.

- Hydraulic hammers: Drive the hammer head through a hydraulic system to provide smoother power and control.

- Roll forging machines: Plastic deformation of metal with one or more pairs of rollers, particularly suitable for the production of parts with long or annular cross-sections.

- Mechanical presses: Generate pressure by crank-link mechanism or screw drive, suitable for die forging and some free forging operations.

- Hydraulic presses: Use liquid pressure to generate thrust and are capable of providing precise pressure control.

- Screw presses: Pressure is generated by a rotating screw, suitable for continuous extrusion and upsetting operations, often used for forging long shaft parts.

- Forging dies: Tools used to plastically deform metal, usually consisting of an upper die and a lower die. Their design determines the shape of the final forged part.

- Heating furnace: Used to heat the metal to the proper temperature to increase its plasticity and make it easier to forge.

- Cooling equipment: After forging, parts usually need to be cooled to stabilize their structure and properties. Cooling equipment includes water tanks, air cooling equipment, and more.

- Conveyor system: Used to transfer metal blocks or forged parts from one workstation to another for different forging operations.

- CNC equipment: In some high precision and complex shape forging, CNC equipment may be used to precisely control the forging process.

Pros and Cons of Forging

Pros

- Superior mechanical properties: Improve the crystalline structure of the metal and increase its mechanical properties such as strength, toughness and wear resistance. Forged products typically have higher strength and hardness, making them more reliable in engineering applications.

- High precision: Provide a high degree of shape and dimensional accuracy, making them suitable for the manufacture of parts requiring precise dimensions. With well-designed molds, complex shapes can be produced that meet design requirements.

- Improved internal structure: Plastic deformation helps to improve the crystal structure of the metal, reducing defects and improving its uniformity and stability. This is critical to improving the performance and life of the material.

- Low material waste: Typically produces less scrap because it forms the desired shape by plastically deforming the metal in a confined space rather than cutting or slashing.

- High applicability: Suitable for a wide range of metals, including steel, aluminum, copper and alloys, making it a versatile processing method.

- Available for large parts: Can be used to make large and heavy parts, such as ship parts and bridge components. Capable of providing sufficient deformation capacity.

- Enhanced controllability: By adjusting parameters such as hammer force, pressure and temperature, the forging process can be better controlled to meet the requirements of different components.

Cons

- Higher cost: Equipment is relatively expensive to purchase, maintain and operate. Especially when working with large and complex shaped parts, custom molds and equipment may be required, which increases production costs.

- Shape limitations: Some complex, small or thin-walled parts may not be as suitable as other processing methods such as casting or cold molding.

- Material constraints: Not all materials are equally suitable. Some metals with high melting points and brittle materials may not be formed by forging.

- Greater energy consumption: The metal needs to be heated, which involves significant energy consumption. Heating at high temperatures not only requires more electricity, but can also lead to environmental impacts.

- Slower production speeds: Compared to some other rapid prototyping processes, forging has slower production speeds. This can be a challenge for some applications that require mass production.

- Die wear and maintenance: Dies can suffer wear during production and require regular maintenance or replacement. This can result in additional costs and production downtime.

- Possible defects: When forging large and complex parts, some internal defects such as porosity and slagging may occur.

Applications

| Industries | Applications |

| Automobile | Engine crankshafts, connecting rods, gears and bearings; Parts for braking systems, transmission systems, suspension systems. |

| Aerospace | High-strength, lightweight components such as aircraft engine parts, aircraft seats and aerospace bearings. |

| Energy | Key components of oil and gas equipment such as pipes, valves, and flanges. |

| Construction and infrastructure | Structural parts such as bolts, nuts, flanges and connectors. |

| Railroad transportation | Rails, hinges and transmission parts. |

| Shipbuilding | Various hull structures, propulsion systems and marine accessories. |

| Military industry | Various weapon systems, armor parts and missile components. |

| Electrical power | Important parts of power plants, such as turbine blades, boiler components and generator parts. |

| Agricultural machinery | Crankshafts, bearings and transmission parts for tractors. |

Conclusion

Forging, as a traditional but powerful metal fabrication process, plays an irreplaceable role in manufacturing. Through the careful plastic deformation of metals, forging not only improves the mechanical properties of the material, but also enables precise control of shape, making it suitable for complex engineering needs in a variety of fields. From automotive manufacturing to aerospace, from the energy industry to infrastructure development, forging has demonstrated its extensive range of applications.

Although forging has some challenges and limitations in its application, its undeniable benefits have made it one of the preferred processes for many manufacturers. Through continuous technological innovation and process improvement, the forging industry has made significant progress in increasing productivity and reducing costs while adapting to modern manufacturing needs.

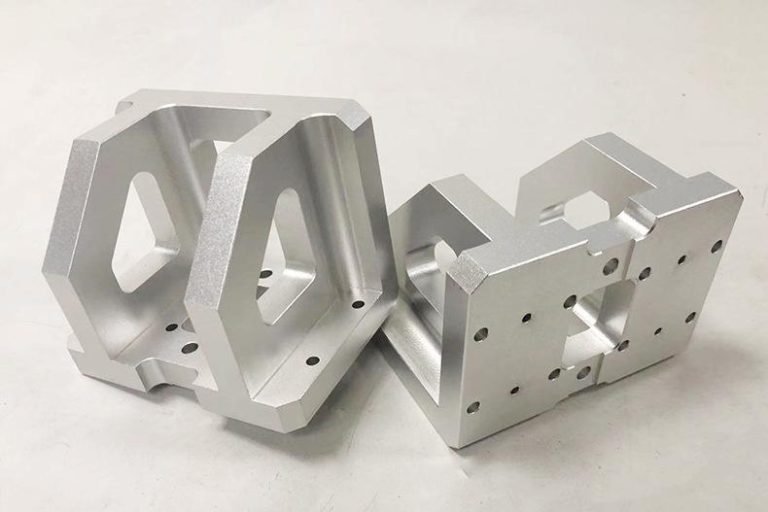

CYCO, specializing in machining and manufacturing for more than two decades, has a unique perspective and strengths in forging machining as well. Whether for small precision production or high volume production, our dedicated team and state-of-the-art equipment can meet your needs. Contact us now!